In the mid-19th century, London was a city of contrasts: a burgeoning metropolis of industry and innovation, yet shadowed by poverty, overcrowding, and social unrest. Amidst this backdrop, a particular form of street crime, garrotting, captured the public's imagination and instilled widespread fear.

Garrotting, in the context of Victorian London, referred to a method of street robbery where assailants would strangle their victims, often from behind, to incapacitate them before theft. While the term "garrotting" has Spanish origins, the practice was not new to Londoners. However, the mid nineteenth saw a resurgence and a shift in public perception, transforming it from a sporadic crime to a symbol of urban decay and moral decline.

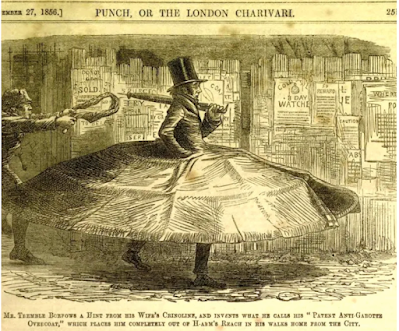

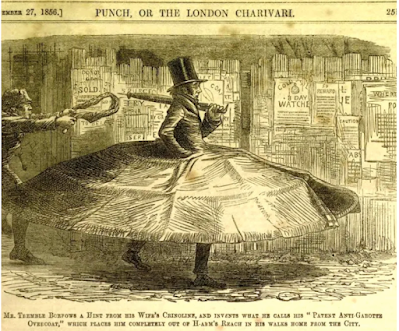

|

| The Anti Garrotte Overcoat, Punch 1856. |

The First Garrotting Panic of 1856.

The initial wave of fear surrounding garrotting emerged in 1856. Reports of such crimes, though not unprecedented, were sensationalized by the press. The public's anxiety was further fueled by the perception that these crimes were committed by foreign criminals, particularly Spanish and Italian immigrants, leading to xenophobic sentiments. This panic led to calls for increased policing and harsher punishments, though the actual incidence of garrotting did not significantly rise during this period.

|

| Anti Garrotting Collars, 1862. |

The Second Garrotting Panic of 1862–1863.

The most intense garrotting panic occurred between 1862 and 1863. A series of high-profile incidents, including attacks on prominent individuals, reignited public fear. Newspapers published lurid accounts, and satirical magazines like Punch depicted exaggerated scenarios of garrotting attacks. The media's portrayal of these crimes as rampant and widespread led to widespread hysteria.

A typical case from the East London Observer, 20th September 1862.

"At Worship Street, Eliza Cooper, Mary West, Mary Ann King, Elizabeth M'Donald, and Elizabeth Simes, all masculine looking women, were charged with stealing £55 in notes and gold from the person of Mr Thomas Roach, a tradesman, at Stepney, on the 22nd August last.

The robbery was accompanied by violence of a very aggravated character, as the prosecutor was knocked down and subsequently rendered insensible by the pressure of the fingers round the throat.

The prisoners were apprehended at intervals from the information of the others, some of whom confessed participation in the crime, while others stoutly denied it. None of the money has, however, been recovered.

All the prisoners were fully committed for trial."

|

| Punch Magazine's Satirical View on Anti Garrot Fashion. |

The garrotting panics revealed much about Victorian society's anxieties. The fear of garrotting was not solely about the crime itself but also about the perceived breakdown of social order. The middle and upper classes, who were the primary victims in reported cases, viewed these attacks as assaults on the sanctity of private life and personal safety.

In response to the garrotting panics, the British government enacted several legal reforms. The 1863 Garrotting Act introduced harsher penalties for those convicted of garrotting. Additionally, the Royal Commission on Garrotting was established to investigate the causes of the crime and recommend measures to combat it. These legislative actions were part of a broader trend of legal reforms aimed at addressing urban crime and maintaining public order .

The press were keen to report these attacks in every detail as they sold newspapers, the truth was that even after the first two "panics" garrotting carried on regardless, here we have a tale from the 12th December 1868;

"John Charles Harvey, 23, vocalist, was charged with having, in concert with three others, garrotted and robbed Mr Charles Edward Ducasse (Naval Captain), of twelve half crowns and a pocket book containing valuable papers.

|

| "and ain't we so precious feared o'bein' 'GARROTTED!" |

The prosecutor said he was a commander in the Bengal Navy, only recently come to this country. He was now living in Limehouse, and early that morning he was proceeding through Commercial Street, Spitalfields, when at the corner of Flower And Dean Street, the prisoner and three others passed him.

Witness then saw the prisoner turn around, and immediately he was seized from behind by him and grasped round the throat, and squeezed so violently that he could not call out. He was then dragged backwards, and the three men, with prisoner, rifled his pockets, of twelve half crowns and also his pocket book, which contained his commission, and other papers.

They also took some papers witness had that morning received from the Secretary Of State, but having looked over them fancied they were of no value and returned them. Afterwards the prisoner released him, and they all ran away up Flower And Dean Street.

Witness called the police, and one came up. While detailing the circumstances to him, witness saw the prisoner come out of the street and walk towards them. He told the officer to take him into custody, when prisoner turned back and ran off. He was, however, caught, and witness gave him into custody.

Corroborative evidence was addressed by a witness named Townsend: and Police Constable Gaen, 143H, said that when he caught the prisoner after a run. Prisoner said, before a word of the charge against him was mentioned, 'I'm quite innocent.' He was then removed to the station."

On the 30th September 1871 a Pawn Broker had an odd story to tell;

"At an early hour on Sunday morning a pawnbroker, named Thomas Cregg, was on his way home, when he was garrotted and robbed of, among other articles, a valuable breast pin. The next morning one of the parties implicated in the theft offered the pin in pledge to the owner, was given into custody, and remanded."

|

| Ally Sloper's Half Holiday - 30th April 1887 |

A decline in garotting incidents, however, did not immediately quell public fear. The legacy of the garrotting panics persisted in the collective memory, as we reached the last two decades of the nineteenth century incidents still occurred.

East End Observer - 15th October 1887.

"Daring Robbery At Mile End.

Thursday night, as Mr C. Kerby, of the firm of Messers, C. and F. Kerby, booksellers of 118, Whitechapel Road,, was proceeding, at about half past ten, to his house in Beaumont Square, four men suddenly sprang upon him.

One pinioned his arms, a second garrotted him, a third put a handkerchief over his mouth, while the fourth snatched at his watch. Fortunately, however, the chain broke, and the watch falling back into his pocket, he only lost a portion of the chain.

His calls for 'Police' were speedily answered, but although a chase was at once given, none of the gang were captured."

Garrotting was an exact science, getting it wrong could potentially be the difference between a prison sentence and the rope, sometimes it did go wrong, Penny Illustrated Paper - 29th October 1892;

"The Borough Outrage.

What appears to be a deplorable case of garrotting ended in the death of the victim, Dr William Peter Kerwain.

This sad story of one of our most dangerous quarters in South London, or an important part of the story, was told by an exceedingly intelligent young witness at the inquest held at Guy's Hospital on the body of Dr Kerwain.

Elizabeth Ann Williams, a little girl of ten years of age, residing at 1, Whitecross Street, said that on Wednesday (Oct. 12), about half past two, she was in Whitecross Street, when she saw the deceased and three other men going down the street.

She called out to a neighbour named Mrs Sweeney, 'Look at those four toffs!' Witness saw that they were going down towards the passage leading towards the George IV Public House, and she expressed a fear to the woman that he three men were going to rob the gentleman. She ran past the passage, and noticed as she passed that the Noble was looking out, while someone was lying down in the passage.

|

| The Doctors Body |

Shortly afterwards she returned, and at once recognised the gentleman lying on the ground as the person whom she said was afraid the men were going to rob. The detectives were lauded for the prompt and able manner in which they captured Charles Balch, Edward Waller, and James Noble, who were charged with the crime at Southwark Police Court after the jury had returned against them a verdict of 'Wilful murder by strangulation.'

A man named Henry Lee was exonerated by the jury, but was included in the grave charge at the police court, where Mr Sims stated that he had confided to a fellow prisoner at Holloway that he had taken part with Balch in garrotting the doctor."

Each one of the gang was sentenced to fourteen years penal servitude, Noble and Lee died in prison, Waller and Balch were released in 1907.

My final example is a crime involving another doctor, details of this event come from this article in the East London Observer, 17th June 1905;

"Doctor Garrotted.

John Doyle, a bootmaker, of 3, St. Ann's Road, Limehouse, was brought up, on remand, charged with being concerned with three other men, not in custody, in assaulting and robbing Dr W. Munro Dazin Gallie, of 12, Ford's Market, Canning Town.

On the early morning of Tuesday week, prosecutor was near the Limehouse Public Library, when someone came out of the shadow and seized him by the throat. He shouted and tried to free himself, and on turning his head saw prisoner's face. Another man got in front of prosecutor, and someone called out, 'settle him.'

The grip on Dr Gallie's throat tightened, and he became unconscious. On recovering, he found a man trying to revive him. He missed his gold albert chain, an oxydised watch, a diamond scarf pin, an umbrella, and a silver cigar case, the whole valued at £80.

He afterwards furnished the police with a description of the prisoner. When the accused was arrested by Detective Sergeant W. Brown of K Division, he said, 'I expect I should get picked up for this job. I saw it in the newspapers, but I know nothing about it. I was stopping that night with Mrs Gilby, of 71, Chapman Street, Watney Street.' Mr Dickinson committed prisoner for trial at the Central Criminal Court."

The garrotting panics of Victorian London serve as a case study in how crime, media, and public perception intersect. While the actual incidence of garrotting was relatively low, the societal impact was profound. These events highlight the complexities of moral panics and their lasting effects on law, society, and collective memory.

No comments :

Post a Comment