1st Volunteer Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers in South Africa 1901 - 1902.

|

| Sergeant Robert Bolton |

The Northumberland Fusiliers were my local regiment, my father was in them, as was my great grandfather and several uncles throughout the 20th century.

My interest in the Boer war stems from my next door neighbour when I was a child, Thomas Bowman was a private in L & M Company (Morpeth) Volunteer Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers (from here on VBNF).

I later found out that my great great uncle Robert Bolton was a Sergeant in E Company (Bellingham) VBNF, he went to South Africa at the same time as my neighbour.

In my last blog I outlined the events concerning the capture of English renegade Frank Pearson, which featured the 1st Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers in the first few months of 1901. Under the overall command of Lord Methuen, and with many other regiments, they were employed escorting convoys and attempting to track down the elusive Boer commandos.

One such action occurred at Kleinfontein on the 24th October, the center of a convoy was attacked by a large Boer force and, taken by surprise, the column was cut in two. The Boers managed to capture some of the artillery guns, but because the horse teams had been shot to pieces so they couldn't be taken away and were soon recaptured.

The rest of the column quickly recovered from the shock and wheeled around to face the Boers, the fighting was intense with many casualties on both sides, finally the Boers broke contact and rode away. They managed to capture 15 wagons of supplies with 150 mules and 160 horses, the British lost 90 killed, wounded and missing, the Boers lost 51.

The Boers were expert guerilla fighters and knew the land intimately well, the convoys of wagons were very vulnerable to attack, stretched over several miles in hostile territory, and the troops protecting them were potentially outnumbered by an elusive enemy.

It was not until 1902 that the 1st VBNF saw any real contact with the Boers, when it came it was fast and brutal, this is their story. I have gleaned the following history from newspapers such as the Morpeth Herald, Newcastle Journal and the Newcastle Evening Chronicle.

Newcastle Evening Chronicle - 3rd January 1902.

"The Fighting Fifth,

The Northumberland Fusiliers, writes a military correspondent, open the new year in a very flourishing state, and it is doubtful whether there be another corps in the service with such a position as that now occupied by the 'Fighting Fifth.' Notwithstanding heavy losses, the 1st and 2nd battalions with the South African Field Force are both over 1,000 strong, while the 3rd and 4th battalions in the Isle of Wight and Ireland are 600 and 700 strong respectively, and have some hundreds of men with mounted infantry battalions at the front.

|

| 1st VBNF on exercise before the war. |

Recruiting at Newcastle depot goes strong, and drafts from the horse battalions leave Tyneside monthly. The mounted infantry section from Newcastle depot is still in training at Aldershot, and is being brought to a fine state of efficiency. Orders for embarkation are expected in a few days.

Brevet-Colonel C.G.C. Money, CB, after having commanded the 1st Battalion for 4 years, about 3 of which he has been on active service, is en route for home, as is also Brevet-Colonel St. G.C. Henry, CB, second in command of the 3rd Battalion, who for nearly 2 years has been commanding a corps of mounted infantry.

|

| Colonel Money and officers of the Northumberland Fusiliers. |

Second-Lieutenant F.R.I. Athill, who has been attached to the 4th Battalion in Dublin, has been ordered to join the 1st Battalion at Lichtenburg."

Meanwhile in South Africa the war went on, it was a very dangerous place for a young inexperienced Tommy. Gifts from home were most welcome, at Christmas the Fusiliers were given a special present.

"The following is a copy of a letter which the Countess Grey has received from Lieut-Colonel Dashwood, commanding the 1st Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers, with reference to the Christmas gifts which were sent out to that battalion:-

Lieut-Colonel Dashwood, commanding the 1st Battalion Northumberland Fusiliers, on behalf of the noncommissioned officers and men of the battalion, and of the company of Northumberland Volunteers attached, begs to thank you the Countess Grey and the Northumberland friends who have so kindly again sent out gifts to them.

He has received a notification from the Standard Bank, Mafeking, of the deposit of £100, which sum will be expended in tobacco. The pipes and handkerchiefs will no doubt arrive by the next convoy, which is expected shortly. The battalion will greatly appreciate these gifts, and still more so the fact that they are not forgotten at home. Lichtenburg, December 24th, 1901."

On the 18th January the latest heroes were honoured in the Newcastle Journal;

"Officers mentioned in dispatches,

The following are honourably mentioned in Lord Kitchener's dispatch:-

Lieut. R.R. Lambton (killed), 1st Durham Light Infantry, 'for most gallant conduct in trying to repulse Boer attack at Blood River Poort, Natal,' on 17th September, 1901.

Sergeant J. Bailey, 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, 'for determination and bravery in Colonel Von Donop's action of Kleinfontein, 24th October, 1901."

A word of warning for those writing to their loved ones, or the press....Newcastle Journal - 5th February 1902.

"The New Volunteer Regulation.

Colonel Gibson On Efficiency.

The regimental orders just issued by Colonel Wilfred Gibson, VD, commanding the 1st VBNF, say that owing to letters having appeared in the press in which individuals have aired their own views concerning the new regulations respecting the conditions of efficiency for officers and volunteers, the commanding officer thinks it desirable to impress upon all ranks of the battalion that he relies on them being guided only by regimental orders on the subject, and giving him every assistance in their power to carry out his orders, which have been and will be carefully considered before promulgation to the battalion.

Owing to the nature of the volunteer force, hardly any two regiments in it are affected exactly in the same way by the new regulations, and Colonel Gibson thinks that some of the opinions given by individuals in the press may have caused members of this battalion to think that the new regulations are impossible to carry out by this battalion. Colonel Gibson is not of this opinion.

He has already given all the officers commanding companies their orders on the subject, and he relies on all ranks to give him and the officers commanding companies their best support in carrying out his orders. So far as recruits are affected there is very little more required of them than what recruits in the past have actually done, therefore the new regulations should not be a reason for the falling off in the number of recruits which the commanding officer fears it is."

Disaster.

Newcastle Journal - 27th February 1902.

Disaster At Wolmaransstad.

|

| Northumberland Fusiliers and New Zealanders at Klerksdorp. |

"Two messages from Lord Kitchener, received yesterday, report severe fighting, and one, we fear, serious mishap. An empty convoy, coming from Von Donop's column at Wolmaransstad, was attacked, about ten miles north of Klerksdorp, and, after severe fighting, was captured.

The escort consisted of the 5th Battalion Imperial Yeomanry, three companies of the 1st Northumberland Fusiliers, and two guns. It was, therefore, a pretty strong force. The message says that no details have been received, but adds that the Boers evidently came from a considerable distance, and are being pursued.

It will be observed that nothing is said as to the fate of the British force and the guns. If the capture of the convoy means that the whole of the escort was taken prisoners, and the guns captured, we must regard it as one of the most serious disasters that has happened for the last month or two.

|

| The convoys stretched for miles and were very vulnerable. |

It may be that the Boers only got the empty waggons; but if that had been so, Lord Kitchener would, we think, have said so; and his formula of 'no details received' generally means the worst. It would appear that this must have been one of those sudden swoops down by De La Rey and Kemp, in which, at various times, they have been exceedingly successful.

The enemy are said to have come from a long distance; and as the site of the affair is far south, and in a neighbourhood where the Boers have not been in force for a long time, we may take it that the column came from the north, and had by night marching suddenly arrived where they were not expected."

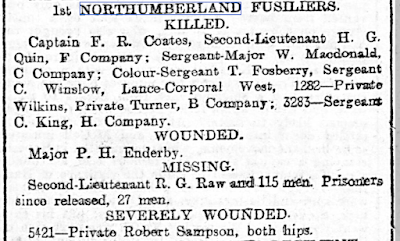

On the 1st March a casualty list was published;

Over the next few days the extent of the disaster was guessed at in the press and mentioned in the House of Commons, the MP's cheered when informed that the 7th New Zealanders had captured 450 Boers the next day in the Klerksdorp area, and that Imperial forces had killed or captured a further 600. In the local newspapers the casualty list kept on growing.

Newcastle Journal - 5th March 1902.

"The War

The Convoy Disaster.

Gallantry of Northumberland Fusiliers.

Klerksdorp, Saturday.

In the extreme rear those of the Northumberland Fusiliers who had been cut off had succeeded in fighting their way out for some distance. Their ammunition had failed them before long, but undismayed they fixed bayonets and charged. Their courage was, however, unavailing against their well armed and mounted foes, and they were eventually overwhelmed.

|

| A depiction of the rearguard action. |

By seven o'clock all resistance was at an end. The dead and wounded lay all over the field, and broken waggons and panic stricken horses and mules made up a scene of indescribable confusion. It was not until General De La Rey came down in person that anything like order was restored.

Numbers of his men were engaged in stripping the wounded, but he at once stopped them by a free use of the sjarabok. He could not be everywhere, however, and the moment he had turned his back the work of despoiling the dead, the wounded and the prisoners was resumed."

Further to that description of the battle, the Newcastle Journal updated it's information on the 7th;

"General De La Rey's attack on Colonel Von Donop's convoy between Wolmaransstad and Klerksdorp was one of the most desperate enterprises he has ever undertaken. The convoy, which was empty, was inspanning after a short rest nine miles from here (Klerksdorp), when the Boers under General De La Rey made a sudden onslaught, their leader's idea evidently being that the convoy was loaded.

The escort, consisting of two and a half companies of Northumberland Fusiliers and 280 Yeomanry, with two 15 pounders and a pom-pom, in spite of the suddenness of the attack, formed up quickly and made a stubborn resistance. The convoy was very large and covered considerable ground, and this circumstance, together with the confusion among the native drivers, and the flurry incidental to the sudden attack rendered the task of defence most difficult.

The escort, however, defended itself gallantly, repulsing the Boers for three hours, when, outnumbered and overcome, the troops surrendered to the convoy. The Boer losses were relatively heavy. The enemy numbered 1,500. General De La Rey behaved kindly to our wounded."

|

| General Koos De La Rey. |

Accounts from private soldiers, the rank and file, began to come in detailing the enormity of the disaster, one witness said;

"We fought like the devil for four hours, but the Boers were too strong for us, so we retired as best we could, all our officers being killed or wounded. We were called upon to surrender, but refused to do so till we saw the game was hopeless. The enemy stripped us of our clothing and left us naked upon the veldt. We were 36 hours without food and shelter."

A member of the Northumberland Yeomanry wrote to his friend in Newcastle;

"We left Wolmaransstad on Sunday morning with an empty convoy and about 600 men, consisting of three companies of Northumberland Fusiliers about 200 strong, the 5th Regiment Imperial Yeomanry, about 200 strong, about 100 of Paget's Horse, a few South Wales Borderers M.I., and a gun escort about 60 in number.

We were riding cooly along, some miles from Klerksdorp, when heavy firing was heard from the bush. Daylight began to break, and we were sent down each flank to guard the convoy. There was no panic. The Yeomanry were mixed with the Fusiliers. The convoy was moved up to the bush, and the Boers then made it very warm at the rear, so those on the right flank were sent thither.

The Boers were mounted, whilst we were on foot. We gave them a few shots, and started to retire, as we saw the convoy was on the move again. The Boers pressed on, and put a very heavy fire into us, which we answered as best we could. The convoy was now galloping, and it was impossible to keep up with it. We were ready to drop.

|

| British soldiers surrender to Boers. |

At last the Boers got close up and charged in among us. At this time the convoy was half a mile ahead, and there was nothing for us but surrender, as we had not a breath left in us. Some of the Boers disarmed us; others galloped on and shot some of the mules to stop the convoy. They took the guns and everything. Some were stripped of their clothing and money. I just lost my coat. General De La Rey used the sjambok (a heavy leather whip) pretty liberally on one man who was stripping the dead.

About 1,500 Boers attacked us, and they and their horses seemed in splendid condition. They were fine fellows to speak to. The youngsters were the worst for taking clothes, ect. General De La Rey was very angry at seeing the men srtipped. Some of the Boers would not think of taking anything without paying for it.

General De La Rey made a speech through his interpreter, as to our treatment of the women and making our prisoners walk. I suppose that is why he only gave us three waggons to carry our blankets when we were escorted back to the line, and we had to walk. De La Rey complimented us on the rearguard action we fought, and before leaving we gave three cheers for the old man, who seemed pleased."

Another disaster.

Lord Methuen Captured, the Battle of Tweebosch.

Newcastle Journal, 11th March 1902.

"House of Commons; Mr Brodrick read a further telegram from Lord Kitchener, dated Pretoria, 11.5 am, giving details of the attack upon Lord Methuen's force by De La Rey.

The Northumberland Fusiliers and North Lancashire Regiment defended the guns gallantly, refusing to surrender until the last. De La Rey's force were almost all dressed in our uniform, making it impossible for the infantry to distinguish our own men from the enemy when the mounted troops were driven in upon them. The enemy's force numbered 1,500, with a 15 pounder and a pom-pom.

Lord Methuen was seen by an officer of the Intelligence Department, and was well cared for. By a private telegram he saw that Lord Methuen had a fractured thigh, but was doing well.

Lord Kitchener hoped that the reinforcements now arriving would rectify the situation in the area without disturbing arrangements elsewhere."

On the 17th March an official version of events was published.

"Pretoria, Sunday, 6.45 am.

Lord Methuen has sent me a staff officer with a dictated dispatch, from which it appears that certain particulars previously given are inaccurate.

The rear screen of mounted troops was rushed and overwhelmed at dawn. There was then a gap of one mile between ox and mule convoys. Mounted supports to rear screen, which Lord Methuen at once reinforced by all available mounted troops, and section thirty eight battery maintained themselves for one hour, during which period convoys were closing up without disorder.

Meanwhile two hundred infantry were being disposed by Lord Methuen to resist Boer attacks, which was outflanking left of rear guard. Boers pressed attack hard, and mounted troops, attempting to fall back on infantry, got completely out of hand, carrying away with them in rout bulk of mounted troops.

|

| Lord Methuen rallying the troops. |

Two guns of the thirty eight battery were thus left unprotected, but continued in action until every man, with the exception of Lieutenant Nesham, was hit. This officer was called on to surrender, and on refusing, was killed.

|

| Canadian Lieut. Nesham |

Lord Methuen, with two hundred Northumberland Fusiliers and two guns of the 4th Battery, then found themselves isolated, but held on for three hours. During this period the remaining infantry, viz., one hundred North Lancashire Regiment, with some forty mounted men, mostly Cape Police, who had occupied a kraal, also continued to hold out against repeated attacks.

By this time Lord Methuen was wounded, and the casualties were exceedingly heavy amongst his men. Ammunition was mostly expended, and surrender was made at about 9.30 am. The party in the kraal still, however, held out, and did not give in until two guns and a pom-pom were brought to bear, about ten o'clock, making their position untenable.

It is confirmed most of the Boers wore our khaki uniform, many also badges of rank. Even at close quarters they were indistinguishable from our own troops. It is clear the infantry fought well, and the artillery have kept the traditions of their regiment. In addition to the forty Cape Police mentioned a few parties of the 5th Imperial Yeomanry and Cape Police also continued to resist after the panic which had swept the bulk of the mounted troops off the ground."

|

| Lord Methuen surrenders. |

One trooper of the 5th Yeomanry said;

"The Colonials bolted as soon as they saw they were outnumbered, and left the Yeomanry and infantry to do the work."

Be that as it may, it was still quite a disaster. Methuen was soon released by the Boers, General De La Rey transported him in his own carriage under a flag of truce to a British hospital, an act for which the Boers tried to court martial him, but he was acquitted.

The biggest British column in the Western Transvaal was now out of action, Methuen was sent home, a wave of sympathy saved his career, a very angry Kitchener was blamed for sending "green" troops to this dangerous area. Kitchener sent in a large force commanded by Colonel Ian Hamilton to sort out the Boers once and for all.

Battle was brought on the 11th April at Rooiwal, a cornered Boer force tried to break out of an encirclement and met well dug in British troops, the outcome was disastrous for the boers, and it signaled the end of the war in the Western Transvaal.

The war ended on the 31st May 1902.

The men of the 1st VBNF were welcomed home in June 1902, my old next door neighbour Thomas Bowman was mentioned in the Morpeth Herald on the 28th June.

|

| Men of the Morpeth VBNF on parade in Oldgate, 1904. |

"The Deputy Mayor had one pleasing duty to perform, and that was to present four young volunteers who had just returned from South Africa, with an illuminated address and a small purse of gold, as a mark of public appreciation of their services. The Deputy Mayor, in a few kindly remarks, presented the addresses and purses to Privates Thomas Bowman, Robert Jewett, J.W. English, and E. Morgan, who were loudly cheered. The Borough Band then played 'God Save The King', which was lustily sung by all present."

|

| A photograph of members of the 1st VBNF taken just after the war, outside the still unidentified Shital House. It was left to me by Thomas Bowman. |

Over in Bellingham my Great Great Uncle Sergeant Robert Bolton was also honoured by having his name included on the town memorial.

|

| The Bellingham Boer War Memorial. |

|

| My Great Great Uncle Robert Bolton, Volunteer. |

|

| The Northumberland Fusiliers Boer War Memorial, Newcastle Upon Tyne. |